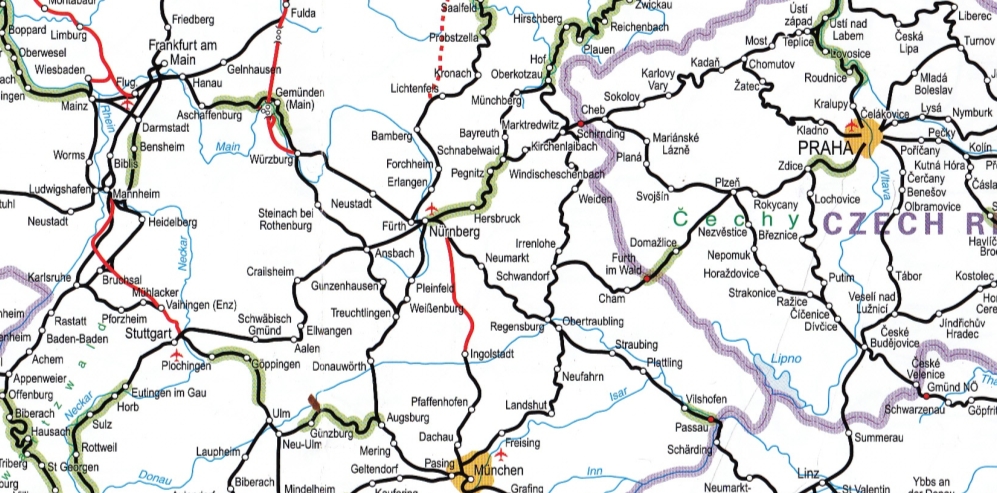

We all know road maps, but few people are aware there also exists such a thing as a rail map. Why would you need a rail map? After all, you are not steering and the train driver knows the way. However, a rail map gives you control over the route you take. In Europe, there are many ways to travel by rail from A to B. If you order a train ticket from Amsterdam to Madrid, for example, the train company will not necessarily offer you the cheapest or most interesting route.

A rail map is especially interesting if you want to avoid high speed trains (which are more expensive), if you make long-distance trips, or if you just love to marvel at spectacular scenery. While an online rail map sounds more modern, nothing beats the convenience of a printed map when you are planning a trip.