The paragraphs below are taken from “100 Deadly Skills: The SEAL Operative’s Guide to Eluding Pursuers, Evading Capture, and Surviving Any Dangerous Situation“, a book that’s not available on WikiLeaks but on Amazon. Written by a retired Navy Seal, Clint Emerson, the book describes skills “which all rely on low-tech or no-tech tools, because complicated instructions are the last thing you need when facing imminent peril”.

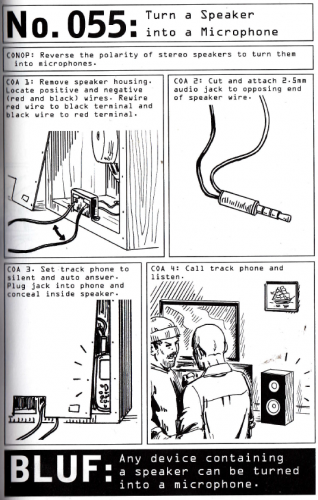

Skill No.55: TURN A SPEAKER INTO A MICROPHONE

“Stashing a voice-activated recording device in a target’s room or vehicle is relatively simple, but without sound amplification, such a setup is unlikely to result in audible intelligence — a proper audio-surveillance system requires amplification via microphone. In the absence of dedicated tools, however, the Nomad can leverage a cell phone, an audio jack, and a pair of headphones into an effective listening device.”

“Stashing a voice-activated recording device in a target’s room or vehicle is relatively simple, but without sound amplification, such a setup is unlikely to result in audible intelligence — a proper audio-surveillance system requires amplification via microphone. In the absence of dedicated tools, however, the Nomad can leverage a cell phone, an audio jack, and a pair of headphones into an effective listening device.”

“Because microphones and speakers are essentially the same instrument, any speaker — from the earbuds on a pair of headphones to the stereo system on a television — can be turned into a microphone in a matter of minutes. The simple difference between the two is that their functions are reversed. While a speaker turns electronic signals into sound, a mic turns sound into electronic signals to be manipulated and amplified…”

“Any small recording device can be employed, but using a phone set to silent and auto answer as a listening device has two advantages: It captures intelligence in real time and does so without the operative having to execute a potentially dangerous return trip on target to collect the device…”

From: “100 Deadly Skills: The SEAL Operative’s Guide to Eluding Pursuers, Evading Capture, and Surviving Any Dangerous Situation“, Clint Emerson, 2015.