A very well documented and illustrated website on the history of everyday home life, housekeeping and domestic objects: Old & Interesting. A few examples:

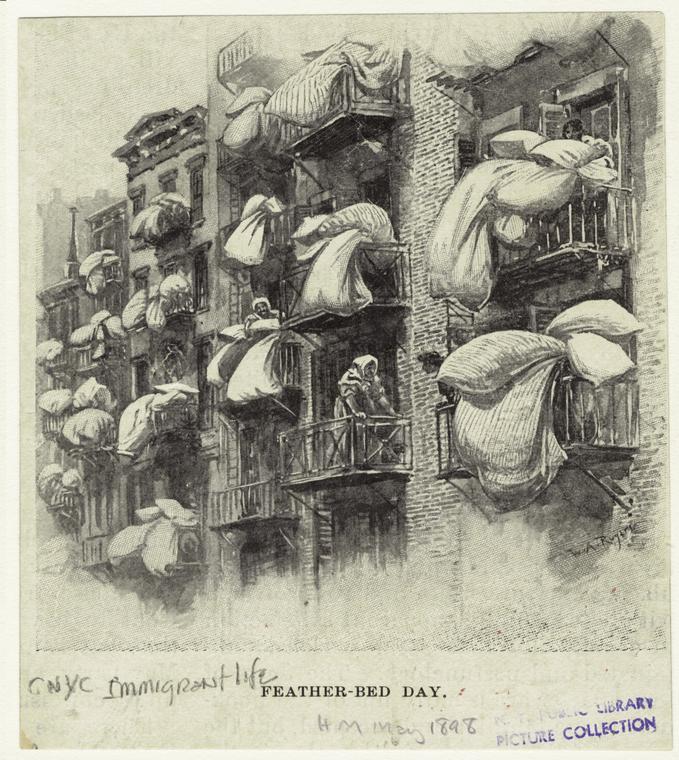

“Featherbeds were only for the rich in the 14th century, but by the 19th century they were a comfort that ordinary people could aspire to – especially if they kept a few geese. The beds, also called feather ticks or feather mattresses, were valuable possessions. People made wills promising them to the next generation, and emigrants travelling to the New World from Europe packed up bulky featherbeds and took them on the voyage. If you didn’t inherit one, you needed to buy up to 50 pounds of feathers, or save feathers from years of plucking until there were enough for a new bed.”

“For centuries in small cottages there were people who could not afford any kind of candle. For them a cheap alternative was a rushlight made from a rush dipped in grease, or a burning splinter of wood. These were held pinched in a nip like pliers or tongs on a stand. Nips were also called nippers or a pair of nips. They could be combined with a candle-holder for people who used both kinds of light, depending on their needs and budget at different times.”

“When you stop and think about it, you probably realise that brooms got their name because they used to be made of branches of broom, a yellow-flowering shrub – except when they were made of birch or heather. Many other shrubby plants have been used across the world for sweeping and brushing. Tie a bundle of good local twigs together, with a tight, narrow grip at one end, and you can whisk dirt away. If you attach the broom to a broomstick, so much the better.”

More: Old & Interesting