“At the time of the Spanish conquest, the Incas cultivated almost as many species of plants as the farmers of all Asia or Europe. On mountainsides up to four kilometers high along the spine of a whole continent and in climates varying from tropical to polar, they grew a wealth of roots, grains, legumes, vegetables, fruits, and nuts.

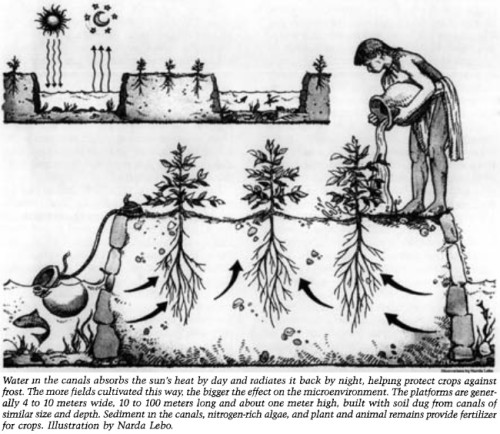

Without money, iron, wheels, or work animals for plowing, the Indians terraced and irrigated and produced abundant food for fifteen million or more people—roughly as many as inhabit the highlands today.

Throughout the vast Inca Empire, sprawling from southern Colombia to central Chile—an area as great as that governed by Rome at its zenith—storehouses overflowed with grains and dried tubers. Because of the Inca’s productive agriculture and remarkable public organization, it was usual to have 3–7 years’ supply of food in storage.

But Pizarro and most of the later Spaniards who conquered Peru repressed the Indians, suppressed their traditions, and destroyed much of the intricate agricultural system. They considered the natives to be backward and uncreative. Both Crown and Church prized silver and souls—not plants.

Crops that had held honored positions in Indian society for thousands of years were deliberately replaced by European species (notably wheat, barley, carrots, and broad beans) that the conquerors demanded be grown. Forced into obscurity were at least a dozen native root crops, three grains, three legumes, and more than a dozen fruits.

Domesticated plants such as oca, maca, tarwi, nuñas, and lucuma have remained in the highlands during the almost 500 years since Pizarro’s conquest. Lacking a modern constituency, they have received little scientific respect, research, or commercial advancement. Yet they include some widely adaptable, extremely nutritious, and remarkably tasty foods.”

Lost Crops of the Incas: Little-known Plants of the Andes with Promise for Worldwide Cultivation, 1989. The book can be consulted online at The National Academic Press.