Frugal Digital is a project that focuses on creating digital solutions in low resource settings like that of developing countries:

“Silicon technology is mostly about a culture of excess. It’s about the fastest, and the most efficient, and the most dazzling gadget you can have, while about two-thirds of the world can hardly reach the most basic of this technology to even address fundamental needs in life—including health, education, and all these kinds of very fundamental issues.”

“We work on projects to set the framework, create tools and provide inspiration for frugal innovators around the globe. Frugality is a way of thinking that optimizes given resources, up-cycles and has the spirit of improvisation. We aim to apply frugality to digital life and create solutions that are inexpensive, adaptable, use available resources and create valuable knowledge along with new solutions.”

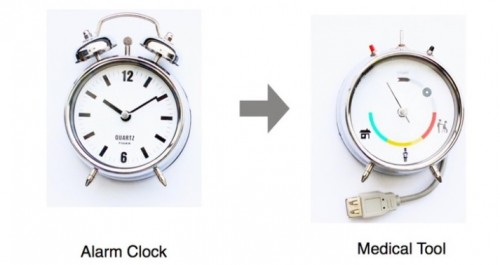

Working with local tinkerers, Frugal Digital already made some interesting machines, mixing parts from different objects. A low-cost cell phone became the heart of a multi-media projector for education, while an alarm clock was rebuilt as an easy diagnostic tool to improve healthcare. Their community radio station introduces “air tweets”.

Via iFixit, who brings more good news for digital tinkerers: there is absolutely no shortage of disposed electronics.