Approximately 5.7 million solid-walled houses exist in England, comprising 25% of the housing stock. Most were built between 1750 and 1914. Research shows that their energy efficiency has been underestimated for decades. [Read more…]

Thermal Insulation of Solid-Walls is Underestimated

Self-Watering Planter From Porous Earthenware

Industrial designer Joey Roth developed a self-watering planter for use indoors or out. It is made from porous unglazed earthenware:

“Soil and plants are placed in the outer donut-shaped chamber, and the center chamber is filled with water. The unglazed terracotta’s natural porosity allows the water to move from the center chamber and into the soil, based on the soil’s moisture (and thus the plant’s need for water). The terracotta wall both regulates and filters the water. A simple lid on the top of the water chamber prevents evaporation.”

The design is based on the Olla, a terracotta pot for irrigation that has been in use for 4,000 years. See also:

The Poor Man’s Refrigerator

“A fridge for the common man that does not require electricity and keeps food fresh too. With this basic parameter in mind Mansukhbhai came up with Mitticool, a fridge made of clay.

“A fridge for the common man that does not require electricity and keeps food fresh too. With this basic parameter in mind Mansukhbhai came up with Mitticool, a fridge made of clay.

It works on the principle of evaporation. Water from the upper chambers drips down the side, and gets evaporated taking away heat from the inside , leaving the chambers cool.

The top upper chamber is used to store water. A small lid made from clay is provided on top. A small faucet tap is also provided at the front lower end of chamber to tap out the water for drinking use.

In the lower chamber, two shelves are provided to store the food material. The first shelf can be used for storing vegetables, fruits etc. and the second shelf can be used for storing milk etc. Cool and affordable, this clay refrigerator is a very good option to keep food, vegetables and even milk naturally fresh for days.”

MittiCool Refrigerator. Thanks for the tip, Joseph. See also:

How to Keep Beverages Cool Outside the Refrigerator

In the industrialized world, we know only of one way to cool beverages: place containers in refrigerators. This practice, which occurs on a massive scale, is utterly dependent on fossil fuels.

In the industrialized world, we know only of one way to cool beverages: place containers in refrigerators. This practice, which occurs on a massive scale, is utterly dependent on fossil fuels.

However, people obtained the same result much more sustainably before the advent of the Industrial Revolution. In hot, dry climates, we used porous earthenware jugs that were not only re-usable, but also kept water cool by taking advantage of natural energy sources.

The best known example is the Spanish ‘botijo’, an unglazed ceramic container that cools beverages by evaporation. Similar drinking containers can be found in other Mediterranean countries, as well as in Mexico (where it is known as a ‘búcaro’) and on the Indian subcontinent (where it is called a ‘ghara’, ‘matka’ or ‘suhari’).

The ceramic water cooler probably originated in the Indus Valley Civilization, which would make it 5000 years old.

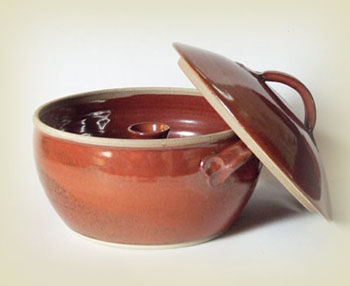

Ceramic Food Steamer With Central Chimney

Steaming food (vegetables as well as fish, meat and rice) is an interesting cooking method, mainly for two reasons: contrary to frying there is no need to use fat, and compared to both frying and boiling less nutrients are lost.

Almost all food steamers or steam cookers on the market work by virtue of many little holes, through which the steam rises from the boiling water below. The disadvantage of this method is that you lose the bouillon of the food, as well as the spices you might add.

Almost all food steamers or steam cookers on the market work by virtue of many little holes, through which the steam rises from the boiling water below. The disadvantage of this method is that you lose the bouillon of the food, as well as the spices you might add.

When I visited my cousin last week in the French Dordogne, I stumbled upon a ceramic steamer in her kitchen. It was hand made by Laurent Merchant, an artisan living and working in the region. Ceramic food steamers are everything but new — they were already used in Neolithic China 6 to 7000 years ago* — but this one was different. Just like any other steam cooker, it is placed above a pot with boiling water. However, the steam enters through a central chimney rather than through dozens of little holes. The obvious advantage is that you don’t lose the juice, which greatly increases the potential uses of steaming.

Some commercially available steamers feature a condensation catchment, but in that case you can only use the bouillon separately, or add it to the food later. Furthermore, the ceramic steamer offers several additional advantages. Its design allows you to easily warm up earlier made dishes or leftovers following the same cooking method, because the device also serves as a perfect storage container and the steam prevents the food from drying out or sticking together. The steam cooker is also particularly suitable for defrosting food, and it is much easier to clean than conventional devices. Last but not least, it is made from sustainable materials and looks great, which cannot be said of most plastic food steamers.

Laurent Merchant did not invent the device, which he dubbed “Le steamer”. Ceramic steamers with a central chimney originated in China, where they might have been in use for many centuries in the region around Shanghai. They resurfaced in California in the 1970s, where the artisan saw them for the first time. I could not find any information on their history, but in 2007 Merchant stumbled upon an authentic Chinese specimen which he could photograph (picture on the right — more pictures here).

“Le steamer” is available in different sizes (from 1 to 4.5 litres) and can be ordered online. Laurent Merchant’s website is in French, but he will answer your questions in perfect English.

* Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5, part 5: fermentations and food science, page 76-91

Traditional Repair Techniques: The Japanese Art of Kintsugi

The Japanese art of Kintsugi, which means ‘golden joinery’ or ‘to patch with gold’, is all about turning ugly breaks into beautiful fixes. Most repairs hide themselves – the goal is usually to make something as good as new. Kintsugi proposes that repair can make things better than new.

Kintsugi is a technique of repairing broken porcelain, earthenware pottery and glass with resins and lacquers that come from trees. It dates from the 15th century. The kintsugi artist carefully repairs the broken vessel with a sticky resin that hardens as it dries. The resin can then be sanded and buffed until the crack is almost imperceptible to the touch. After that, the artist takes a lacquer that has been combined with real gold and covers the crack.

Check it out: 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5. The first link mentions a couple of DIY-kits using cheaper binding materials.