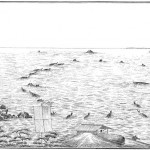

“Hoping to cultivate a better understanding of where the food on our plates comes from, Tomm Velthuis designed a toy farm highlighting the unsustainable reality of the meat industry.

The wooden set, called Playing Food, comes complete with 200 pigs, the enormous amounts of food required to fatten them up, the trees that must be cleared for feed crops, and the acid rain caused by the pigs’ manure. It’s factory farming packaged as an ‘innocent’ childhood toy.”

See more pictures at Tomm’s blog. The farm is on display at mEATing-kill your darlings, an art event about our relationship with meat and animals in Tilburg, the Netherlands. See also: Can I see your Meat License?