The passive solar bird bath provides some unfrozen water in the winter for the birds to drink. Its a nice simple design that is easy to build. The sun shines through the glazed panel on the south side of the pedistal and warms a solar absorber which heats the bird bath from below during the day. Jim got the idea from passive solar horse watering troughs. Find the building plans at BuildItSolar.

The Motorized “Solution” to Harvesting Wheat in Nepal

Three short videos demonstrate how an ingenious (and centuries old) adaptation of the scythe for harvesting wheat beats simple tools and high-tech alike.

Three short videos demonstrate how an ingenious (and centuries old) adaptation of the scythe for harvesting wheat beats simple tools and high-tech alike.

Steve Leppold writes us:

Here’s an example of a low-tech approach that is clearly superior to the motorized “solution”; and yet the expensive, fossil-fueled “upgrade” is being successfully marketed in developing nations like Nepal and India. One man from Canada is attempting to bring some sanity to the situation.

- The current “no-tech” method.

- The low-tech approach, being demonstrated in Nepal by Alexander Vido.

- The motorized “solution” that is being promoted by agricultural agencies.

Alexander Vido and his teenage son brought donated equipment to Nepal in 2012, and made this short video of their volunteer efforts. The project is described at Scythe Project in Nepal.

Thanks, Steve. The project’s website has lots of technical information. Previously: The Religion of Complexity.

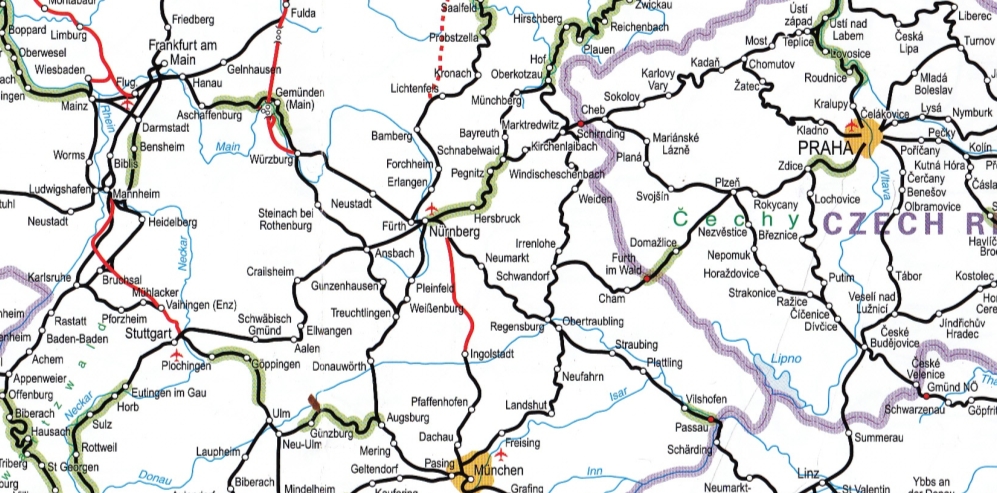

The Complete Guide to European Rail Maps & Atlasses

We all know road maps, but few people are aware there also exists such a thing as a rail map. Why would you need a rail map? After all, you are not steering and the train driver knows the way. However, a rail map gives you control over the route you take. In Europe, there are many ways to travel by rail from A to B. If you order a train ticket from Amsterdam to Madrid, for example, the train company will not necessarily offer you the cheapest or most interesting route.

A rail map is especially interesting if you want to avoid high speed trains (which are more expensive), if you make long-distance trips, or if you just love to marvel at spectacular scenery. While an online rail map sounds more modern, nothing beats the convenience of a printed map when you are planning a trip.

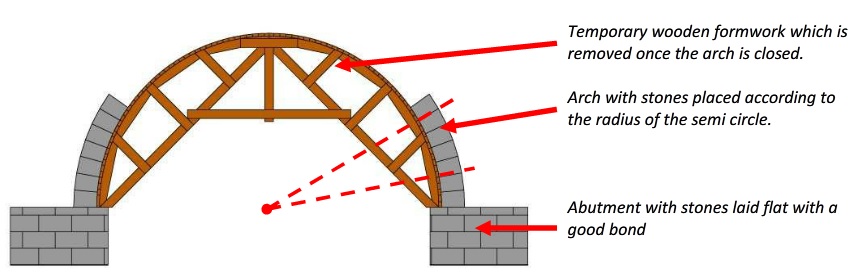

Stone Arch Bridges

“Stone arch bridges are amongst the strongest in the world. The technology has stood the test of time. The Romans built stone arch bridges and aqueducts with lime mortar more than twenty centuries ago. Arches and vaults were also the determining structural design element of churches and castles in the Middle Ages. There are stone arch bridges which have survived for hundreds and even thousands of years, and are still as strong today as when they were first constructed.”

“The main reason that western countries moved away from stone arch bridges is because of the high labour costs involved in their construction. In industrialised countries, it is cheaper to use pre-stressed concrete rather than employ a lot of masons and casual labourers. In the economic environment of East Africa and the majority of developing countries, stone arch bridges provide a more affordable and practical option.”

“A larger proportion of locally available resources are used in stone bridges as they can be built with local labour and stones. In contrast, raw materials and machines have to be imported for the construction of concrete bridges and specialized expertise is required. Compared to expensive aggregates, local stones are a strong, affordable material and they are often available in the vicinity (10-15 km) of the construction site. There is no need for expensive steel bars, aggregates, concrete or galvanised pipes that have to be hauled over long distances.”

Stone arch bridges, a strong and cost effective technology for rural roads. A practical manual for local governments, BTC Uganda & Practical Action.

Related:

Low-Tech Music: One String Guitar

Brushy One String – Chicken in The Corn (Official Video). Hat tip to Sara.

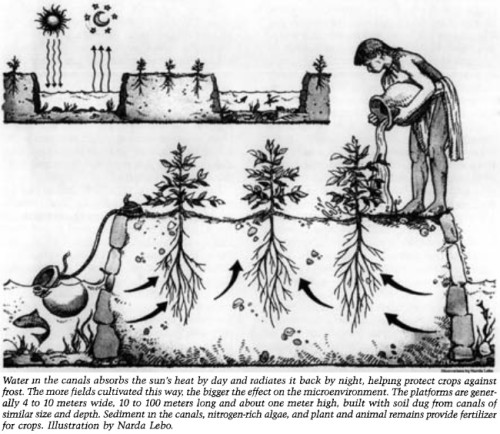

Lost Crops of the Incas

“At the time of the Spanish conquest, the Incas cultivated almost as many species of plants as the farmers of all Asia or Europe. On mountainsides up to four kilometers high along the spine of a whole continent and in climates varying from tropical to polar, they grew a wealth of roots, grains, legumes, vegetables, fruits, and nuts.

Without money, iron, wheels, or work animals for plowing, the Indians terraced and irrigated and produced abundant food for fifteen million or more people—roughly as many as inhabit the highlands today.

Throughout the vast Inca Empire, sprawling from southern Colombia to central Chile—an area as great as that governed by Rome at its zenith—storehouses overflowed with grains and dried tubers. Because of the Inca’s productive agriculture and remarkable public organization, it was usual to have 3–7 years’ supply of food in storage.

But Pizarro and most of the later Spaniards who conquered Peru repressed the Indians, suppressed their traditions, and destroyed much of the intricate agricultural system. They considered the natives to be backward and uncreative. Both Crown and Church prized silver and souls—not plants.

Crops that had held honored positions in Indian society for thousands of years were deliberately replaced by European species (notably wheat, barley, carrots, and broad beans) that the conquerors demanded be grown. Forced into obscurity were at least a dozen native root crops, three grains, three legumes, and more than a dozen fruits.

Domesticated plants such as oca, maca, tarwi, nuñas, and lucuma have remained in the highlands during the almost 500 years since Pizarro’s conquest. Lacking a modern constituency, they have received little scientific respect, research, or commercial advancement. Yet they include some widely adaptable, extremely nutritious, and remarkably tasty foods.”

Lost Crops of the Incas: Little-known Plants of the Andes with Promise for Worldwide Cultivation, 1989. The book can be consulted online at The National Academic Press.