The Meseta Central is a vast plateau in the heart of Spain with long, cold winters and short, scorching summers. The locals say that there’s “nine months of winter” and “three months of hell”. The region has little trees, so heating (and cooling) has always been a challenge.

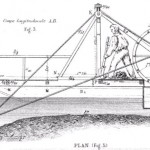

In the early middle ages, the Castillians developed a subterranean heating system that’s a descendent of the Roman hypocaust: the “gloria”. Due to its slow rate of combustion, the gloria allowed people to use smaller fuels such as hay and twigs instead of firewood. [Read more…]