Quoted from: Cederlof, Gustav, and Alf Hornborg. “System boundaries as epistemological and ethnographic problems: Assessing energy technology and socio-environmental impact.” Journal of Political Ecology 28.1 (2021): 111-123.

What are the social and environmental impacts of carbon and low-carbon energy technologies in different places and at different times? To answer this question, we are faced with an epistemological dilemma. Before measurement takes place, we need to define where and when the phenomenon we are measuring begins and ends—to define its “system boundaries.” For instance, one liter of semi-skimmed milk, bought in a British supermarket, has an energy content of 380 kcal. However, to think of the milk in terms of energy also evokes the far-reaching social and environmental contexts that bring milk to the market.

Beyond the energy content declared on the milk carton, we can undertake a life cycle assessment (LCA)—expanding the system boundaries—to account for the energy (or the carbon, water, labor, or land) “embodied” in the milk via its production and distribution. We might include the energy content of processed cattle feed, electricity used to run milking machines, cooling tanks, water boilers, and lighting, energy inputs in alkaline and acid detergents, diesel for tractors, and a wide range of other energy technologies used in production.

We might expand the system boundaries further to account for the fuels needed to generate the electricity, run the chemical plant, fuel the milk tanker, power the dairy plant, and so on. Arguably, we should also account for the energy expended in the production of the electricity generator, the milking machine, the milk tanker and the tractor, fencing and the batteries storing energy to electrify it. But if an electricity generator and a battery are somehow embodied in a liter of milk, we have culturally come far away from what we normally understand milk to be. Where, then, should we draw the system boundaries around an object in order to gauge its social and environmental impact?

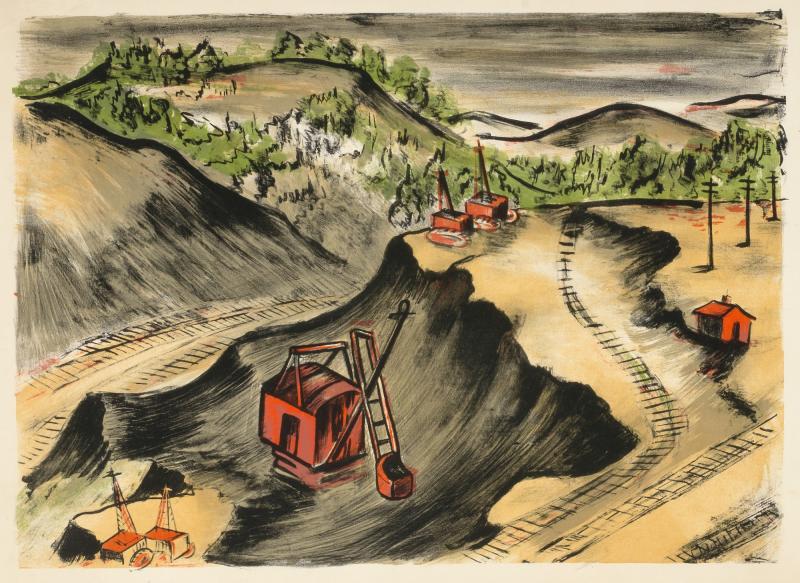

More than just posing epistemological problems, however, we argue that system boundaries present an ethnographic problem and that they should be exposed to cultural as well as political analysis. As cultural artefacts, system boundaries sustain different power-serving worldviews, and the way system boundaries are drawn in discussions on energy transitions calls into question how the existence of energy technologies relies on a geographical displacement of environmental load, including flows of resources, land, and emissions.

In discussions on green development and strategies for a low-carbon energy transition, there is a strong case made for technologically utopian solutions in which novel, more efficient technologies will enable a decoupling of environmental impact from economic growth. These solutions range from a complete electrification of transport to the mainstreaming of “cultured” meats, milk, and eggs to a wholesale transition to a solar economy. Depending on the exponent’s political allegiance, they often resonate with teleological imaginaries of technological progress inspired by the American “technological sublime” or the Marxist “development of the productive forces”. However, the socioenvironmental impact of green technology is contingent on the definition of system boundaries. A technologically utopian solution rests on narrowly defined system boundaries.

Read more: Cederlof, Gustav, and Alf Hornborg. “System boundaries as epistemological and ethnographic problems: Assessing energy technology and socio-environmental impact.” Journal of Political Ecology 28.1 (2021): 111-123.