“Early shelters were built of availale materials. Hides spread over poles or the bones and tusks of mammoths formed a type widely used. Stone and clay were common early building materials. Usually there was only a single room, with the fire located at the center of the living area. In many parts of the world this pattern changed little from the earlies times right up to the present. Smoke escaped from such dwellings as it could, through the low door or a smoke hole in the roof… The Scots developed a special word, snighe, for rain that worked its way through the roof sods and dripped down black with soot upon the people below.”

“Today the term stove refers to a certain kind of container for fire; the stove warms the room. In earlier times stove meant the heated room itself… The dwelling was a container for the fire that burned on the open floor. A hole in the roof let the smoke out. The door admitted air for combustion, just as the adjustable air inlet does today on the door of an iron stove… The beehive houses of Scotland’s Western Isles, and the central-hearth houses of Ireland, normally had two doors. Whichever door lay on the side away from the wind was used to adjust the draft. American Indians did much the same with their tipis, lifting the skins on one side as a draft adjustment for the fire that lay on the open floor.”

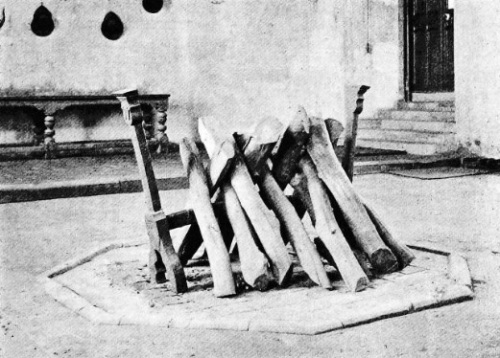

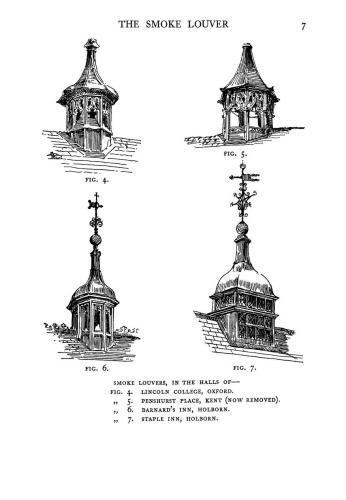

“Sometimes, as in Scandinavia, there was a louver in the roof, a kind of trapdoor that could be closed and opened with a pole. During the early and smoky stages of the fire the louver was opened. It was closed to keep the heat in after the fire had burned down to charcoal and offered little smoke. In the manors and larger buildings of England, louvers became quite elaborate architectural features. Instead of simple trapdoors, they took the form of cupolas. These blocked the rain but let out the smoke in winter and the heat in summer.”

“Sometimes, as in Scandinavia, there was a louver in the roof, a kind of trapdoor that could be closed and opened with a pole. During the early and smoky stages of the fire the louver was opened. It was closed to keep the heat in after the fire had burned down to charcoal and offered little smoke. In the manors and larger buildings of England, louvers became quite elaborate architectural features. Instead of simple trapdoors, they took the form of cupolas. These blocked the rain but let out the smoke in winter and the heat in summer.”

“The atmosphere in the central-hearth building depended on various factors, including the design of the building, weather, the quality of fuel and its moisture content, and the skill of the firetender. By present-day standards, conditions must have left a good deal to be desired… Still there were real advantages to the chimneyless house. The fire on the floor offers all its heat to the room; it is 100 percent efficient. The chimneyed fireplace offers a meager 10 percent efficiency as a rule, channeling 90 percent of the heat outdoors.”

“The central hearth also saved woodcutting at a time when woodcutting tools were poor. Long sticks could be fed gradually into the fire. And there was room for more people close to the warmth. Many continued to use the open hearth, including some of the colleges of Oxford, long after the chimney became known.”

Quoted from “The Book of Masonry Stoves: Rediscovering an Old Way of Warming“, David Lyle, 1984.

The illustrations are from “The English fireplace: a history of the development of the chimney, chimney-piece and firegrate with their accessories, from the earliest of times to the beginning of the XIXth century“, 1912. It talks about smoke louvers (or smoke turrets) on pages 5-9.

Related: Well-tended fires outperform modern cooking stoves.