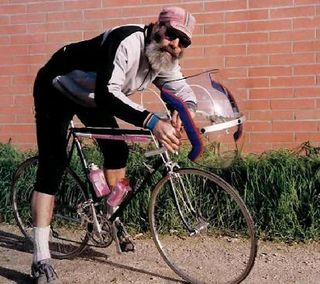

“In the early days of bicycle racing there was a time when plucky riders took on long hard races alone with no team cars and soigneurs to look after them. They were hardy and desperate men who ate what they could find, slept when they could and rode all day. They weren’t professional athletes or men of means, they were “mavericks, vagabonds and adventurers” who picked up a bicycle and went to seek their fortune.

The founders of the Tour de France wanted to create a race of thousands of miles of cycling, whatever the weather and road conditions where “even the best will take a beating” Often they would race long into the night to distances of over 400 km each day in stages that would take more than 18 hours. Henri Desgrange, the father of the tour once noted that “the ideal Tour would be a Tour in which only one rider survives the ordeal.”

Somewhere along the way from a variety of influences, the grand tours changed to become what they are today; a race of the elite, held apart from the common cyclist by budgets, sanctions and industry. Don’t get us wrong, the Grand Tours as they are now are great and exciting things. We however also like the old way where a rider can simply pick up a bike, shake hands on the start line and race thousands of miles for the pure satisfaction of sport and no other motive but for the learnings of one’s self.”

The Transcontinental is a low impact, self supported cycle race. Now in it’s 4th year, it will travel between Geraardsbergen in Flanders and Canakkale in Turkey passing through control points in the Auvergne region of France, Switzerland, the Dolomites in Italy and Durmitor national park in Montenegro. Entries for 2016 are closed, but the organisers are looking for volunteers, who will be eligible for a priority application in next year’s race.